What makes a good term paper?

Five Hitchcock Rules

Introduction

Writing term papers is more of a craft than an art. That is to say, there are relatively clear criteria for what makes a good term paper; and there a skills you can learn to hone and eventually master this craft.

This document describes what I think makes a good term paper. Other teachers will have slightly different expectations and preferences. But just like the journey(wo)men of yesteryear, it is part of your academic apprenticeship to learn from different ‘masters’ - even if they have a slightly different perspective on what the tricks of the trade are.

This document is written in that spirit. It comes in three sections. The first section describes the ‘5 Hitchcock Rules’ for writing good term papers. The second section gives an overview of the main types of term papers. The third section provides a glossary of miscellanea.

The ‘Hitchcock Rules for Good Writing’

Loosely adapted from the cinematic philosophy of Alfred Hitchcock, we can formulate 5 rules for good writing.1 These are:

Have a good opening. Your introduction should excite the reader and capture their attention.

Suspense and not surprise. Introduce your research question (and answers) early and clearly; don’t be a mystery writer.

Keep the story simple. Don’t do too many things or things that are too complicated.

Communicate clearly. Avoid jargon and try to use visualizations to aid your writing.

Every shot counts. Erase what you don’t need.

Rule 1: Have a good opening

The purpose of an introduction is to make the reader keep reading - just like the point of a movie opening is to get the viewer keep watching. This requires you to do three things:

Make it clear why your topic matters. A topic matters if it’s about something of societal importance or addresses an important academic debate. Ideally, it matters to both the public and your academic ‘peers’.

Make clear what your argument and contribution are (see also, Rule 2). What is the point you’re making, how will you make this point, and what does it add to existing debates?

Make clear how your paper is structured. Give an overview of the sections of your paper so the reader knows what to expect or where to look for what.

Rule 2: Suspense and not surprise

There is no reason to leave the reader in the dark about what you’re actually doing. You should introduce your research question very early, probably on the first page. You should also briefly summarize your main arguments and findings early on. This is not to say that you have to give away everything. All the juicy details are best presented in the main parts of the paper. But don’t entirely surprise the reader either. He or she has to know what’s coming, just not precisely enough to not want to keep reading. There is a great quote by Hitchcock that illustrates the differences between suspense and surprise:

“There is a distinct difference between ‘suspense’ and ‘surprise’. I’ll explain what I mean. We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let’s suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden,”Boom!” There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions, the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene.”

Let your argument or findings be the bomb. The reader kind of knows what’s coming. But all of a sudden, they pay more attention to your ‘innocuous’ theoretical argument or empirical setup because they read it with the ticking bomb in mind.

Rule 3: Keep the story simple

There is a tendency, especially but not only among students, to put everything in one paper: everything they’ve read, everything they find interesting, everything that might somehow matter. Don’t do this. Think of your reader not as a connoisseur of art-house films but more like an average moviegoer: most likely, they won’t appreciate overly complicated, fragmented, or convoluted storylines.

Try to stick to a fairly narrow question - one you feel like you can answer in less then two-thirds of the space you are given. Believe me, you will still need it all. Also, avoid asking too many sub-questions. No one minds a good side-plot, but there shouldn’t be too many and they should relate to your main story. Hitchcock knew that, and you should too!

In the same way, try to give an answer that is as complicated as necessary but as simple as possible - not the other way around. Sometimes things are complicated. You don’t need to force reality in the Procrustes Bed of a simplistic story. But keep in mind that understanding or explaining a piece of social reality means simplifying it in an argument that focuses on one or a few key features - it does not mean listing everything that could possibly be of relevance.

Rule 4: Communicate clearly

The dumbest thing academic writers do is to try and sound like academic writers. Great writing is communicating complex ideas in simple language - not to further mystify them. As the saying goes: write to express, not to impress. And be aware, stylistic restraint is easier preached than practiced. As John Gardner is said to have said, ‘writers that love language always have to restrain themselves a little, like compulsive jokers at a funeral.’

There are a few rules of thumb that can help you become a better writer. Note that these are not rules that apply always and to everyone. Excellent writers can and do ignore them successfully. But as always in life, don’t try at home what professionals do for a living.

Write short sentences (for a caveat, see below). Not every sentence needs a relative clause. Most do not need more than one. If you have a tendency to write long sentences, just make periods where you’d otherwise have commas. You might feel like a first-grader, but in reality you become a first-grade writer!

For the most part, avoid words that you have only seen in academic papers and nowhere else. Avoid words like perspicacious, purport, or verisimilitude like the plague. Trying to sound smart and having something smart to say are often inversely correlated.2

Try to avoid cluttered expressions. Don’t say “a certain number of”, say “some”. Don’t say “for the purpose of”, say “to”. Don’t say “if this is not the case”, say “if not”. Don’t say “in the event of”, say “if”. You get the gist.

Cutting words of works wonders. Take these examples:

Use fewer words

in orderto make your pointstronger.Remove unnecessary words

that you don’t needin sentences

Try to use simple verbs instead of these weird noun constructions. Don’t write “give consideration to”, simply write “consider”. Don’t write “perform an assessment of”, simply write “assess”. Don’t write “for the maximization of”, simply write “for maximizing”. Again, you get the gist.

Try to use as many examples as possible. Generally speaking, if there is not an example on at least every third page, you’re doing something wrong. Examples also help you think through what you want to say. Use them or lose the reader.

Use diagrams, figures, or data plots to underscore, illustrate, or summarize your point. Hitchcock was a master of visual storytelling. Try to become one as well.

Use the active voice whenever possible. No one would say “The ball has been kicked by me” instead of “I kicked the ball”. But for some reason, academics say “The argument was made by X et al that” when you could just say “X et al. argued that”. Don’t be that person!

Try to mimic your speaking voice, just without the ums and errs. It’s okay, of course, to be a bit more eloquent in your writing than in your speaking. But try to read out loud what you wrote, and if it sounds awkward and clumsy, rewrite it.

Rule 5: Every shot counts

Hitchcock was adamant that every shot counts. If a shot did not add anything to the movie, it should not be in the movie. Take that advice to heart when you write - but especially when you rewrite - your paper. In fact, the old adage that one should write without fear and edit without mercy has a lot to it.

Don’t be surprised if cutting sentences or - Heaven forbid! - entire paragraphs is painful. It is meant to be. But the price is worth the pain. Don’t be afraid to kill your darlings - once they’re gone, you’ll rarely miss them.

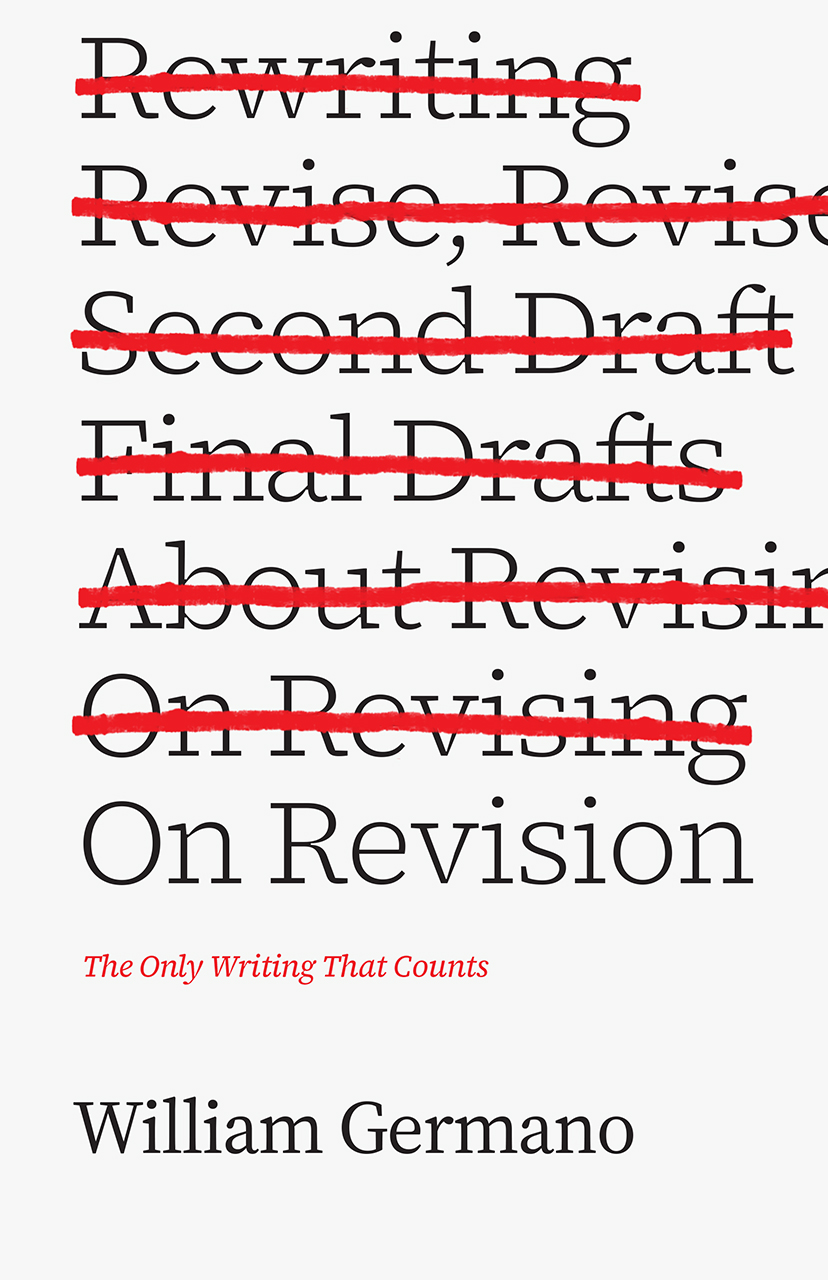

Gustave Flaubert once said that prose is like hair; it shines with combing. And for Robert Graves there is no such thing as good writing; only good rewriting. Take this as an encouragement. It’s okay when your first draft is not great, but it’s not okay if you submit your first draft. And if you don’t believe me, I highly recommend this:

Main Types of Term Papers

In principle, term papers can come in many forms, including essays, research plans, and policy briefs. However, only under exceptional circumstances will I accept papers that don’t fall into one of the following categories:

Problem-oriented literature reviews summarize and systematize the literature on a certain topic from a certain point of view. They are not a list of all the things you’ve read on a topic. Rather, they review the literature on a certain topic with a specific question in mind and try to find common threads or competing schools of thought in that literature. For example, if you’re interested in the rise of platform work, you don’t write a paper summarizing a bunch of papers that have been written on this topic. Rather, you focus on a specific question or problem within that literature, such as: what determines whether or not platform work is regulated? You may then identify different arguments in the literature, with some focusing on the business power of the digital platforms, others on institutional differences between countries, and yet others on framing effects and discursive battles. You can then organize your literature review along these lines.

Theory-based empirical studies come in two varieties: theory-based case studies and theory-based quantitative studies. Both start from a question that needs an empirical answer. The former may ask, for example, why platform work was (not) regulated in a given city or country. It then reviews the literature on that question in a more focused manner than in problem-oriented literature reviews. Based on that, it develops certain theoretical expectations (e.g., the institutional structure of the labor market should be very important for whether platform work is regulated and for how it is regulated). Informed by these expectations, it then ‘goes into the field’ and investigates whether these expectations bear out empirically. If not, maybe there is a competing theory that is better suited to explain the case, or perhaps an entirely knew theory is needed. Case studies can take many forms. They can, for example, compare two cases that are very different but show the same outcome; or two cases that are very similar but show different outcomes; they can look at an ‘easy case’ where we would expect the theory to be correct; or a ‘hard case’ where the theory is least likely to be correct. The empirical work will often be based on policy documents, newspaper articles, but perhaps also on newly acquired data such as interviews or documents obtained through freedom of information requests.3 Quantitative studies also start with the theoretical literature but develop more explicit hypotheses that can then be tested in statistical analyses. For example, one might hypothesize that platform work is more common in geographic regions where unemployment is high. One can then test whether unemployment on the regional NUTS-3 level actually predicts the prevalence of platform work, controlling for other factors.4

Empirical mappings do not have a causal or correlational ambition but want to describe empirical patterns. For example, one could be interested in wage differences between different types of platform workers. Empirical mappings require less theoretical work, but they often require more conceptual work in return. This is because mapping something requires one to carefully operationalize what is being mapped. For example, how can we categorize different types of platform workers? By skill level? Type of occupation? Structure of the platform? Empirical mappings also require more empirical work. It might, for example, not be easy to find good data on the wages of platform workers. But this is part of the exercise. Empirical mappings can of course - and will most often - use data that already exist. But these data may be a bit harder to find, to clean, or to organize than finding out how much revenue a platform company had in a given year. As a rule of thumb, when one can find what a mapping paper wants to do in less than 5 minutes on Google, it’s probably not a good paper.

Glossary of Miscellanea

There are many more things that make a good (term) paper. Here’s a short - and by no means exhaustive - glossary.

Abstracts

Writing good abstracts is essential - for every person that reads your paper, there are often many more that read your abstract (although that is perhaps not true for term papers). Fabrizio Gilardi provides a great template for a good abstract; I don’t have anything to add to it.

Everyone agrees that this issue is really important. But we do not know much about this specific question, although it matters a great deal, for these reasons. We approach the problem from this perspective. Our research design focuses on these cases and relies on these data, which we analyze using this method. Results show what we have learned about the question. They have these broader implications.

Structure

If you are unsure how to structure an academic research paper, I’ve found this extended hourglass model quite useful (even though it might be a bit restrictive for some types of research).

Fonts

Fonts matter - they make things easier and more pleasant to read and avoid confusion (see below).

Formatting

Let’s face it, humans like to look at pretty things. It’s a basic point, but hard to deny. It’s also true for papers. Papers that are nicely formatted, with easy-to-read fonts, with good spacing, and a clear and elegant design are something that I look forward to reading. Awkward fonts on cluttered pages that give off a ‘my-uncle-did-this-in-word-2003-vibe’ don’t elicit that feeling. There are plenty of decent formatting options out there, whether you use Word, Quarto, LaTeX, or something else. Make sure to pick one!

Variety & Rhythm

There is a danger to writing with too many short sentences. Once you get more confident with your writing, you can therefore experiment with combining short, medium, and long sentences. Gary Provost’s example below shows how playing with sentence length can create rhythms that can almost transform text into music:

This sentence has five words. Here are five more words. Five-word sentences are fine. But several together become monotonous. Listen to what is happening. The writing is getting boring. The sound of it drones. It’s like a stuck record. The ear demands some variety.

Now listen.

I vary the sentence length, and I create music. Music. The writing sings.

It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony.

I use short sentences.

And I use sentences of medium length.

And sometimes, when I am certain the reader is rested, I will engage him with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that burns with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals–sounds that say listen to this,

it is important.

Some more writing advise

Footnotes

I remember hearing about these rules many years ago, but neither do I remember any details nor who I heard it from.↩︎

This is not to say that certain academic concepts aren’t valuable or even essential. Their use is absolutely justified, even if they are rarely heard outside ivory towers. These concepts, however, should be well defined and not be used casually. Examples include institutions, discourse, or salience.↩︎

Note that such extensive data collection is never required and is usually a sign of excellent work.↩︎

Note that this example requires data that may not exist.↩︎